A comparative study of punctuality for passenger trains in different European countries considers that countries with high demand for train traveling could be a driving factor in achieving reliable railway systems with high punctuality. The study indicates that punctuality at an overall level is better in countries that invest more in railway infrastructure. However, it states that it is difficult to make detailed comparisons of punctuality because the definitions of punctuality differ.

A comparative study of punctuality for passenger trains in different European countries considers that countries with high demand for train traveling could be a driving factor in achieving reliable railway systems with high punctuality. The study indicates that punctuality at an overall level is better in countries that invest more in railway infrastructure. However, it states that it is difficult to make detailed comparisons of punctuality because the definitions of punctuality differ.

As a part of the Swedish Parliament’s investigation concerning punctuality for passenger trains EPF’s board member Emil Frodlund has conducted the section consisting of a European comparison. Since 2007 the European Commission has been collecting railway statistics through questionnaires to the member states and Norway. Attempts have been made to achieve greater uniformity to enable more relevant comparisons. However, punctuality data may still differ in the following aspects:

- It is unclear if the statistics cover only performed departures or include all planned departures (i.e. also canceled departures).

- There are still different time limits for what counts as punctual even if the aim is to apply a similar definition. It also differs in terms of rounding to minutes, if it occurs at half minutes or include all seconds until the next minute.

- Data can either include punctuality for the train measured at several places along the line or only at the arrival station.

- There is no harmonized definition of train types (long-distance trains, regional trains, etc.).

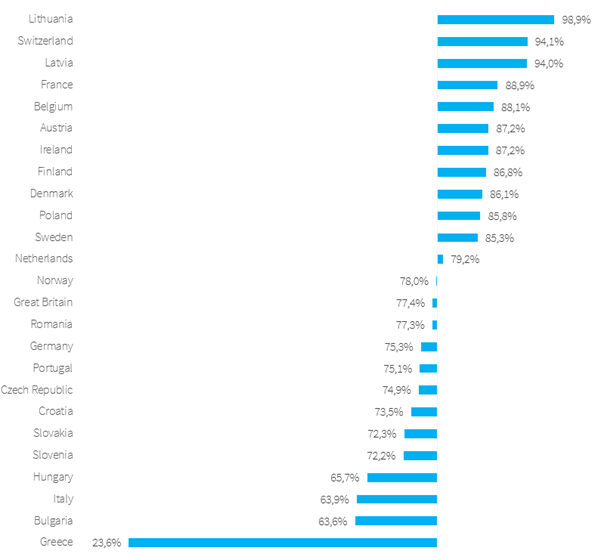

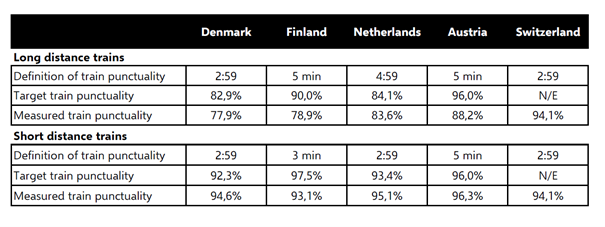

The diagram below shows the punctuality of long-distance trains with the definition of a maximum of 5 minutes delay, except for Switzerland, which applies a narrower definition of punctuality, a maximum delay of 2 minutes and 59 seconds. The values indicate the average punctuality for the years 2015 and 2016. Switzerland does not report any division of statistics between long-distance and medium- or short-distance trains. The Baltic countries have railway networks with very low traffic volumes, so there is lower risk of disturbances in the system when a train is delayed, which may be an explanation for the high punctuality figures in Lithuania and Latvia.

Punctuality for long-distance passenger trains (max. 5 min. delay except for Switzerland) – proportional distribution. Source: European Commission Rail Market Monitoring Survey, 2019 (processed with data on Switzerland).

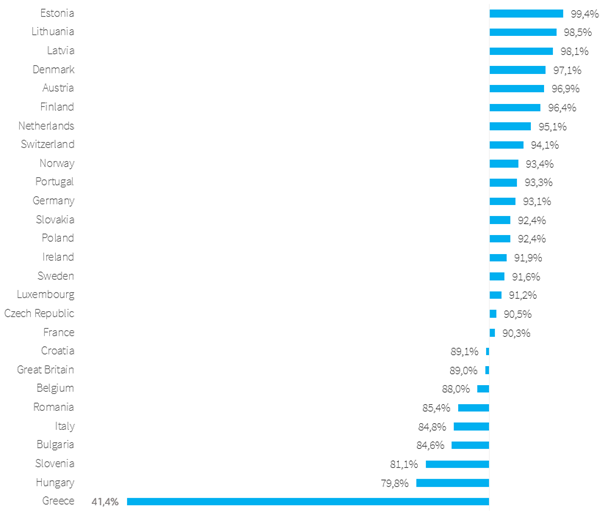

The diagram below shows the punctuality of medium- and short-distance passenger trains a maximum of 5 minutes delay except for Switzerland, which applies a narrower definition of punctuality, a maximum delay of 2 minutes and 59 seconds. The values reflect the average for punctuality for the years 2014, 2015 and 2016. Since Switzerland’s definition of punctuality is narrower, a maximum of 2 minutes and 59 seconds delay, Switzerland is underestimated in the comparison. The high punctuality figures in the Baltic countries could be explained by low traffic volumes in the railway systems.

Punctuality for medium and short-distance passenger trains (max. 5 min. delay except for Switzerland) – proportional distribution.

Source: European Commission Rail Market Monitoring Survey, 2019 (processed with data on Switzerland).

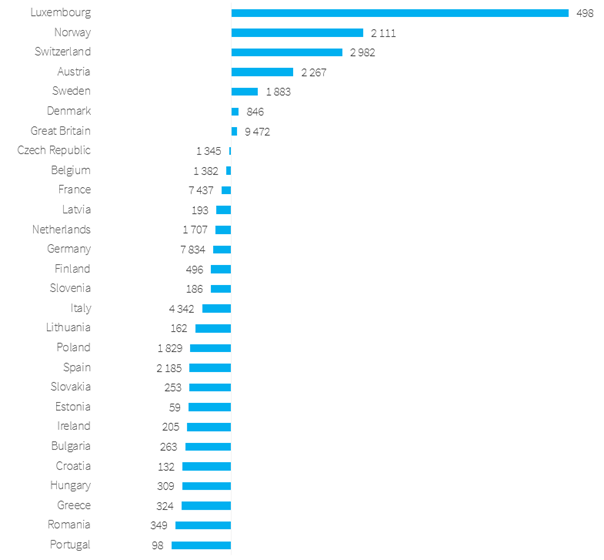

The diagram below shows the proportional distribution of the investments in maintenance and new railway infrastructure per capita in the countries 2016. Comparing investments per capita between countries can be interesting because it can give an indication of the extent to which the countries are investing in the railway infrastructure. However, the comparison only reflects investments in a given year so it is difficult to draw quick conclusions. The length of the bars represents the proportional distribution of investments per capita in relation to the other countries. The center line corresponds to the countries’ proportional average. Note that the numerical value at the bars indicates the de facto investments in millions of euros for each country.

Proportional distribution of countries based on investments in railway maintenance and new infrastructure per capita 2016. The numerical value at the bars indicates the de facto investments in million Euro for each country.

Source: European Commission Rail Market Monitoring Survey, 2019 (processed with data for Switzerland).

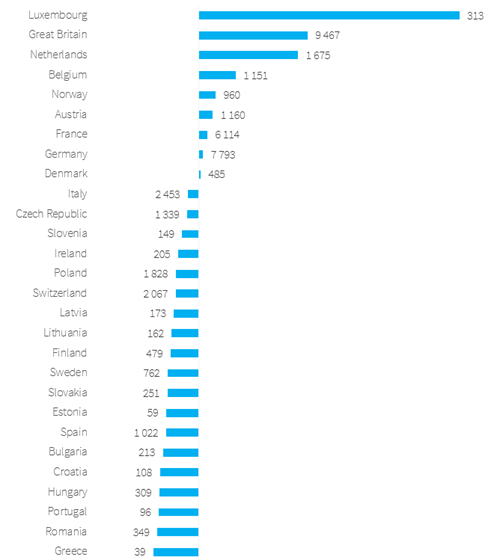

If study the proportional distribution only for investments in railway maintenance distributed per track kilometer the outcome will be quite different. The numerical values next to the bars indicate the de facto investments in million Euro for each country.

Proportional distribution of countries based on investments in railway maintenance per track kilometer 2016. The numerical value at the bars indicates the de facto investments in million Euro for each country.

Source: European Commission Rail Market Monitoring Survey, 2019 (processed with data for Switzerland).

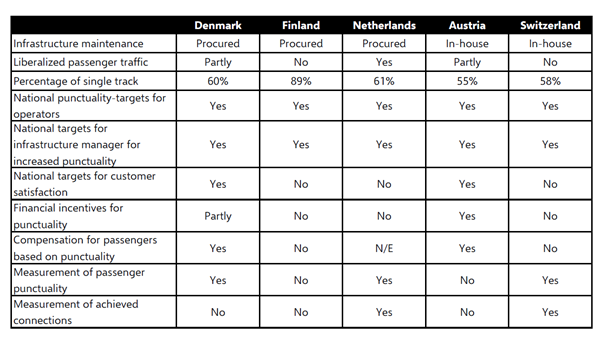

The assignment also included an in-depth study in which the situation in Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Austria and Switzerland was mapped with a focus on organization, governance, follow-up and measures to increase punctuality among the actors in the railway sector.

The majority of the governments in the countries studied had explicit targets for punctuality directed to infrastructure managers or operators. Another finding was that countries such as Switzerland and the Netherlands, which have a very high capacity utilization and are likely to have greater challenges in achieving high punctuality, nevertheless exhibit very high punctuality. There is reason to assume that increased demand for train traveling can be a driving factor for countries to create good conditions for achieving reliable systems with high punctuality. The methodology for collecting punctuality statistics in Switzerland and the Netherlands, where the proportion of delayed passengers, not just the proportion of punctual trains, is measured, could also be a contributing factor to the need for a more reliable railway system in general.

The Netherlands has succeeded in reducing the number of traffic disruptions and shortening the time for recovery in the event of a traffic disruption, despite the fact that the number of trains has increased by 25% over the past decade. The government regulates both the management of the railway infrastructure and the operation of the main railway network through 10-year concession agreements, where there are performance indications for punctuality that are followed up annually with some possibility of demanding sanctions. Since 2015, data has been published on the proportion of passengers who arrive on time in addition to statistics on train punctuality. This is made possible by the fact that all train traffic in the Netherlands are part of a common ticket system where passengers check in and out at the stations.

In Switzerland, there is a political will to transfer freight transport from lorries to railways. Lorry taxes are therefore used to finance railway maintenance and cover two thirds of the costs, which amount to around EUR 2 billion annually. Since the beginning of the 1980s, the railway network has been planned on the basis of a so-called Taktfahrplan (which means that connecting trains can be reached with short changeover times). This has required high precision and punctuality in the system, which may have been a contributing factor to Switzerland has become a pioneer in punctuality. Switzerland is also developing AI support for the traffic management aimed at minimizing the risk of the human factor resulting in unfavorable decisions. By carrying out simulations for a large amount of disruptions scenarios, it is possible to predetermine optimal solutions for the railway traffic management.

In Austria, the government regulates 10-year transport agreements with operators where follow-up on punctuality is the most important quality criterion. The agreements have an incentive structure in the form of a bonus – malus system where target values are stated for measured punctuality and perceived punctuality where the latter is based on customer satisfaction evaluations. ÖBB Infrastruktur has given priority to address bottlenecks and remedy sections of tracks with low speed limits and has extended the competence of the staff in the mobile maintenance teams to facilitate troubleshooting and be able to solve problems more quickly in case of urgent infrastructure problems. In Austria, punctuality has been improved nationally through increased cooperation with neighboring countries to minimize disruptions from delayed trains from abroad. ÖBB Personenverkehr has increased the number of employees in order to provide better customer information in the event of traffic disruptions.

In Finland, the government applies financial incentives in the form of bonuses to the Director General of the Finnish Transport Administration and special managers in the organization linked to compliance with performance indicators such as punctuality. The state railway operator VR emphasizes the importance of making accurate vehicle procurements to ensure high operational reliability even in winter conditions. VR plans for additional resources prepared to shovel snow from locomotives and wagons in the winter. In Finland, detailed punctuality statistics are available via open data and VR has an interactive map service where all trains and delays can be tracked in real time.

Train commuters in Denmark can register to take part in the state owned operator DSB’s compensation program. For each percent less punctuality compared to the promised level, DSB compensates the commuters with 1 percent of the price of the season ticket. Compensation is paid automatically to the passengers’ bank account.

The entire investigation in Swedish can be found below. The European comparison is on p.211-280.

Emil Frodlund

Stay informed!

Stay informed!